The urinal that precipitated modern art

How a misattributed sanitary fixture kick-started an artistic movement.

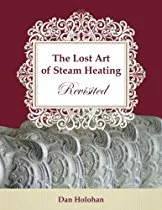

Figure 1: “Blind Man 2,” May 6, 1917. Richard Mutt’s urinal, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz, April 14, 1917.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

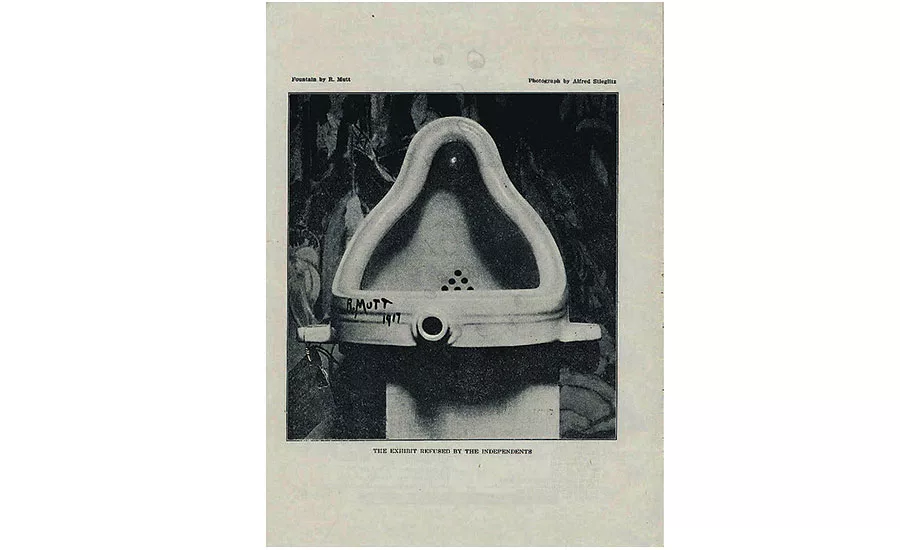

Figure 2: Mott’s Plumbing Fixtures, Catalogue “A,” 1908. The J. L. Mott Iron Works building at Fifth Avenue and 17th Street, Manhattan, New York City, 1906-1928. All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

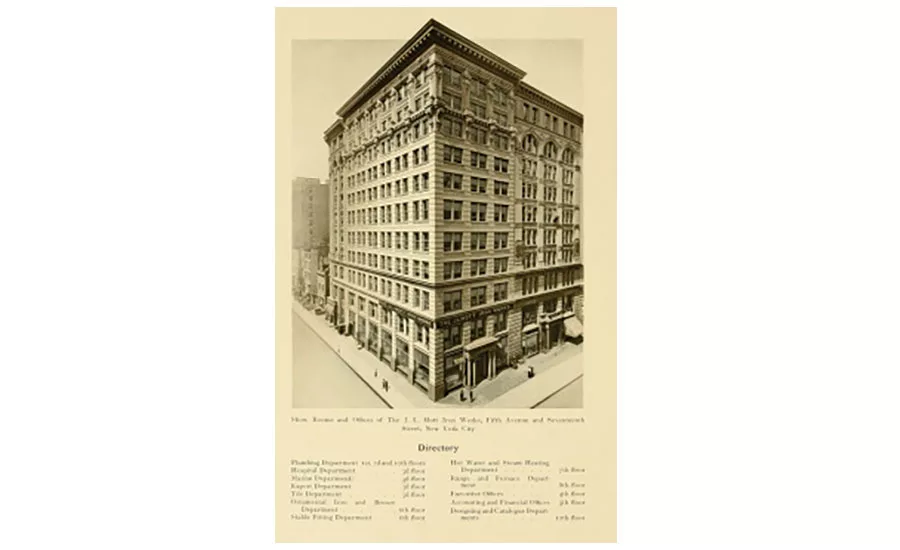

Figure 3: The Trenton Potteries Co. The Blue Book of Plumbing, Catalogue “N” October 1915, page 177, Plates 3755-N and 3765-N.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

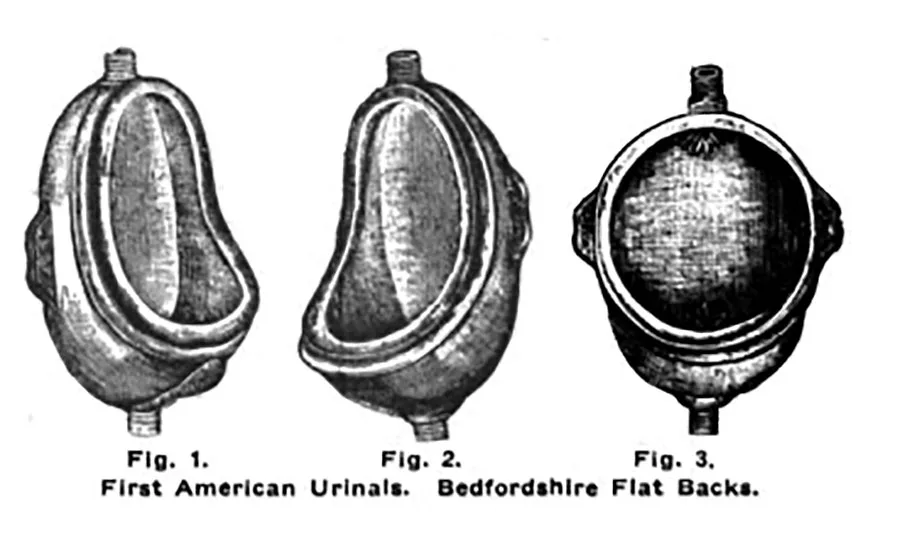

Figure 4: Charles Weelans. Lavatories and urinals: First Types. Engineering Review. March 1910. Thomas Maddock’s first urinals.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

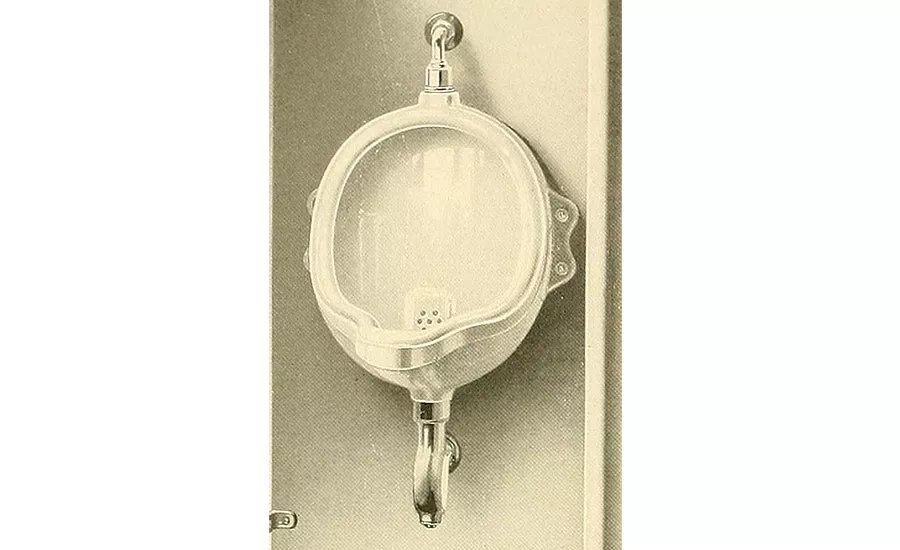

Figure 5: J. L. Mott’s Plumbing Fixtures catalogue “A” 1908: Plate 6592-A. The “Bedfordshire porcelain urinal.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

Figure 6: Trenton Potteries “Bedfordshire” flat-back lipped urinal No. 2, 1915-1920. Coll. Dr. G. Thompson.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

Figure 7: Henri-Pierre Roché. May 1918. R Mutt’s urinal in Duchamp’s studio, 33 West 67th St, NYC.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

Figure 8: Death mask of Baroness Elsa von Freytag- Loringhoven. Marc Vaux, transition, February 1928.All photos courtesy of Glyn Thompson

Since the role played by plumbing in the history of modern art in America has largely escaped the attention of its critics, it would be no surprise it has also failed to fascinate its plumbers, who consequently might be intrigued to learn that the most influential work of art of the twentieth century was a urinal.

Sent under the pseudonym “R. Mutt” to an exhibition in New York on April 9, 1917 — and rejected because Mutt was not a member of the exhibiting society — this ‘submission’ would be misconstrued as demonstrating that art could be anything that an artist said it was, resulting in the colonization by “conceptual art” of galleries from Memphis, Egypt, to Memphis, Tennessee.

This allegedly radical gesture — one that overturned traditional art making — was then misattributed 18 years later to one Marcel Duchamp (1883-1968), but no evidence existed then or now to suggest or confirm that Duchamp had, in fact, been responsible.

In 1982, contemporary evidence from Duchamp’s own hand unexpectedly surfaced and disqualified him. This letter, sent to his sister in Paris, stated plainly that not he but a female friend had sent the urinal to exhibition.

But, secure in the delusion the letter that could expose him had apparently disappeared, in 1966 Duchamp would claim that he had obtained the urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works at Fifth Avenue and 17th Street in Manhattan — which would have been impossible, for the following reasons.

First, the Mott catalogue from April 1917 didn’t include the rejected urinal, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz in 1917, and from 1908 all J. L. Mott publicity reiterated that all the plumbing fixtures that it sold it manufactured itself — and this one it didn’t.

Second, vitreous porcelain urinals could be obtained from a manufacturer only by plumbing supply houses, which sold to contractors and master plumbers — not avant-garde artists.

Third, the seven floors of the J. L. Mott building at 118-120 Fifth Avenue (see Figure 2) that were accessible to the public consisted entirely of showrooms from which, as with automobiles, no direct retail purchases could be made, since their exclusive function then, as now, was to display — and many showroom fixtures were under pressure.

And, finally, the urinal in question had actually been made by the Trenton Potteries Company (TPCo) of Trenton, New Jersey, and manufactured in its particular size between 1915 and 1920, but in a smaller size range from 1892 to 1922. This was the Vitreous China Flat-back Lipped “Bedfordshire” No. 2 (See Figure 3) — by 1917, “Bedfordshire” urinals had for decades been made in three almost universally standard sizes.

As the master plumbers of America will be aware, the “Bedfordshire” was the most basic, simplest and cheapest of wall-hung earthenware urinals, the first examples made on and of American soil — copies of English imports — being manufactured by Thomas Maddock in Trenton in 1873 (see Figure 4).

There was, in fact, a “Bedfordshire” model in the Mott inventory (of seven urinals) in 1917 (see Figure 5), but it cannot be confused with the TPCo example since the two clearly differed in critical details.

First, the unique combination and style of perforated ventilator and integral strainer of the Trenton Potteries’ “Bedfordshire” cannot be mistaken for that of the Mott, nor of any other design or make of urinal. And second, the Mott model incorporated a patent overflow that the Trenton Potteries model clearly lacked.

While the system whereby urinals were manufactured, marketed and distributed in the U.S. in the period running up to and beyond World War 1 invalidated Duchamp’s claim, it simultaneously made it easy for his female friend to stroll into any of the scores of high-street plumbers’ shops in Philadelphia — where she resided and from where the rejected urinal would be sent to New York — and pick up a urinal cheaply, for the article in question had suffered a fault in its burning that rendered it useless to a plumber.

This is revealed if an actual example of the urinal (see Figure 7) is compared with another photograph taken of the same article in the summer of 1918, showing it hanging from the ceiling of Duchamp’s studio.

But the fault can only be identified by those who know what they’re looking at, which means that to unravel this conundrum you need to consult Joe the Plumber, who can tell you that the fault had occurred at the dynamic fulcrum of the pattern where the perforated ventilator and the integral strainer meet at the seam joining the back of the urinal to the bowl — rather than a Duchamp ‘expert,’ who can’t.

Mutt’s urinal’s actual author was not exactly a “nobody,” though. On the run from the NYPD for shoplifting, cross-dressing quick-change artist Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven had fled to Philadelphia from New York in January 1917. Astonishingly, the daughter-in-law of the German Kaiser’s Chief of Staff lived precariously on the fringes of the art world, scratching a living as a model, shoplifter and possibly prostitute.

But because she was a woman, she would be written out of the boys’ club of modern art. And since she died in 1927 in relative obscurity (see Figure 8), she wasn’t around in 1935 when her urinal was misattributed by Andre Breton to Duchamp.

Breton failed to cite any evidence in support of his claim. No surprise there, because none exists.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!