Plumbing Essentials — Design Approaches, Codes and Everything in Between | Lowell Manalo

The process behind seamless water heater selection

Creating a decision making process.

My house water heater recently failed. The existing water heater was a 50-gallon storage-type gas heater. It’s an older house with no recirculation system. I want to replace the old one with something more efficient, like a heat pump.

The easiest path would be to replace it with the exact same type. It would be cheap and involve little downtime and hassle. It would be a quick fix, and would for good for another 10 to 15 years, but where's the fun in that?

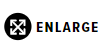

What would you do if you had a similar scenario with a client or project? Would you pick the most straightforward path? Or be more adventurous and go through systematic planning first, even if you are aware of what the outcome may be. I choose the latter. See Figure 1 for a sample of a planning process I used to replace a water heater. This column does not address the findings in detail, since many resources are available when comparing water heater types, etc. The intent is to highlight the process.

FIGURE 1

1. Important factors to the client

We need to understand the essential factors that affect the client's decision. I am the client in this scenario, and the water heater's cost and efficiency are important to me. Downtime is not important to me in this situation. Another essential item of information is that the existing water heater stand, and the lower part of the wall/drywall must be replaced. I intend to replace this myself, which is also a significant factor in decision-making.

2. Research and discovery — phase 1

This is just a high-level side-by-side comparison of different types of water heaters. It might be a fundamental comparison, but it is sometimes the most challenging step for those like me who have over 20 years of experience in the industry, as we tend to develop our own biases to specific systems, and sometimes, we refuse to entertain or look for new options out there.

There are so many factors in selecting water heaters. There are different types, such as storage, tankless, solar and heat pumps, to name a few. Also, we need to consider sources such as natural gas, electricity, geothermal energy, fuel oil, etc. Additionally, plenty of options now exist, such as automation, etc. However, with the age of my house and the electrical modifications needed, heat pumps don’t make sense financially. Does this mean I must abandon my support for a more efficient system? What else can I do if an electric type or heat pump is not an option?

Knowing that I must use the same source, which is natural gas, I need to find other means for better efficiency. That’s when I started to look at the storage type vs. tankless options.

The above example might be straightforward, but the process can be applied to all systems and decision-making outside of the design industry. The components of this process are unique and different for each person and scenario. Just have fun, create your process and learn from it.

3. Research and discovery — phase 2

At this point, the tankless type has already been identified. This stage examines available options and compares different tankless manufacturers and models. Now, we need to look at all of the available features for tankless and identify options that I need vs. unnecessary items to save cost. The existing hot water system does not recirculate or return to the line, so I don’t need the features associated with the return line. Knowing that my house does not have water treatment, I started looking for tankless water heaters with options to help in addressing the hard water here in Arizona.

4. Stress test

To me, this is a crucial phase. This is my last chance to challenge the outcome of the abovementioned research and discovery phase. I will throw multiple darts at the idea, challenging the concept's validity, feasibility, and constructability. I mentioned the stress test before in my July column titled, “Designamus Defendimus.”

During this process, I discovered that I forgot one crucial detail: most of the tankless options I was looking at come with a 3/4-inch gas supply. My existing gas line is 1/2-inch and modifying my existing 1/2-inch gas line to 3/4-inch is an additional cost and not acceptable to me. This set me back to the Research and Discovery Phase.

The above example might be straightforward, but the process can be applied to all systems and decision-making outside of the design industry. The components of this process are unique and different for each person and scenario. Just have fun, create your process and learn from it.

I enjoy this process. It allows me to stop and pause. The journey, to me, is more enjoyable than the destination. We must learn to detach ourselves from the outcome and enjoy the process. Only then will you enjoy the journey.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!