Avoiding the pitfalls of breaking concrete with above-floor grinder pumps

Alternative plumbing solutions to fit your customers' needs.

Image Source: waaruchch / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Undoubtedly, you've often found yourself in the following predicament: A property owner needs restroom amenities or a commercial kitchen in a location without existing plumbing, or where the nearest plumbing line is several feet away. They call on you for an inspection, evaluation and cost estimate. The challenge? It is either very expensive to cut the floor open or even impossible to achieve.

Faced with the inevitable of creating below-floor drainage, either through conventional plumbing or sewage ejection, it quickly becomes apparent that breaking through concrete is necessary. This approach, however, is messy, noisy, time-intensive, and expensive. So expensive, in fact, that your quote may very well lead the client to reconsider the project entirely.

For trade professionals, navigating concrete obstacles is just another day at the office. Yet, for others, it might be less welcome. Regardless, it's often seen as par for the course in this line of work. Should a client be deterred by the involved hassles, you simply move on to the next project.

Fortunately, there is a viable, cost-effective solution to the laborious process of trenching: the above-floor drain pump system. Above-floor grinder pump systems are not only convenient but also offer significant cost savings. However, faced with the scenario described, many plumbers overlook this alternative, likely due to unfamiliarity.

But, even if above-floor plumbing technology is new to you, it's worth contemplating the serious risks associated with breaking through concrete floors. These are concerns worth discussing thoroughly with your client before embarking on such a project... and perhaps considering a less invasive method.

Red flags to remember

Cutting concrete undermines structural integrity: Any time you cut into a slab, you decrease the foundational integrity of the building — no matter how close to a perfect cut you make. You may be able to patch the hole you create well enough to eliminate any aesthetic objections from your customer. But is that floor as solid as it was before you began to cut? We would bet not — especially if you fail to use the same or a better grade of concrete. And if the building sits on ground that’s less than solid, such as sand, it may begin to settle differently after the cut.

In a multi-floor building, cutting into a slab on the second, third, fourth levels to run plumbing beneath the floor would be a huge no-no. That’s why commercial-renovation projects that require additional plumbing will typically use external soil stacks, putting the external plumbing tree on the outside of the building. Well, if you shouldn’t cut into any of the upper levels of a building, why would you think you could safely cut into the first-level — the slab on which everything else sits?

Cutting concrete is unpredictable: Installers don’t always know the depth of the concrete, whether it sits on rocks or a ledge, or whether it contains rebar or tension cables. You can cause major damage if you accidentally cut one of those cables. Professional contractors understand this hazard and never begin cutting without first using an x-ray machine to determine the positioning of the cables.

But even then, the slab was most likely designed to use a certain number of cables with a certain amount of concrete. If you begin removing chunks of concrete, those tension wires may begin pulling in a different direction, creating integrity problems and causing delays and extra expense.

Cutting concrete is seldom, if ever, perfect: You may try as hard as you can to cut a perfect circle, square or rectangle into a floor for burying a sewage ejector and its waste-storage basin — but no way. That “perfect” shape will inevitably crack on the edges and fray outward in unintended directions, often well beyond the hole you’re digging. And once a stress crack is created, how far down does it extend into the footing or into the walls?

Cutting concrete creates leaks and seepage: Once a stress crack is generated, radon and ground-water penetration is a major issue, with the latter bringing unwanted moisture and mold problems as well. You don’t need a major flood to trigger these hazards. A higher-than-usual water table because of extended wet weather, such as in the spring, could be the culprit. Even if the cracks and seepage are not large enough to jeopardize the foundation, enough wetness could infiltrate to ruin walls, floors and furnishings in a finished living area — including that beautiful new bathroom that necessitated digging through the concrete in the first place.

Cost factors: Last, but certainly not least, there’s the problem we mentioned at the outset of this article, the one that often proves to be the biggest deal-breaker of all: cost. The actual expense of cutting concrete depends on the size and complexity of the job, as well as local labor availability and rates. In some parts of the nation, the per-foot rate may be $1,000 or more.

Seeing these costs, some plumbers outsource the work and are content to make little or no markup on their sub’s charges. Others, preferring to keep the job in-house, absorb the time and cost of renting the cutting and hammering tools and lugging them on and off the job site; or, if they choose to buy, the cost of maintaining and replacing these tools, as well as depreciation.

Perhaps the biggest and most painful expense of all is the “lost-opportunity” cost. With above-floor plumbing, creating a new bathroom or kitchen where none exists usually takes a day, maybe two at most, to install the basic plumbing. Go the busting-through-concrete route and you’ll be on the job triple or quadruple that amount of time and likely more. What other work could you be doing all those extra days — more profitable work that you like much better and are really good at — instead of wrestling with broken concrete and all the hassles it brings?

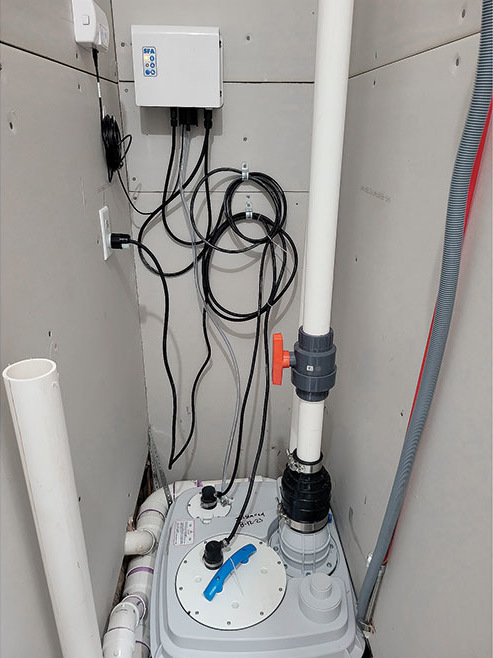

The Sanicubic 1 VX is a 1.5 HP, heavy-duty Vortex system that pumps wastewater from several bathrooms in a single structure. It can remove waste up to 36 feet vertically through a 2-inch diameter pipe; or up to 20 feet when discharging through a 4-inch pipe. Image courtesy of Saniflo

In this application, the wastewater from two bathrooms and the kitchen sink feeds into the vortex pump unit. The unit pumps the wastewater vertically via a pipe located in the attic space. Then, it travels with a 1/8 per foot slope to the main sewer line outside the building, discharging a total horizontal distance of 30 feet. The pumping unit is conveniently located in the small storage closet, a central location that serves all fixtures efficiently. Image courtesy of Saniflo

Above-floor grinder pump systems as an alternative

No doubt, installing conventional plumbing requires major construction. In fact, based on the pitfalls shared above, it could be even more expensive and complicated if your customer’s space is in an older building or a high-rise, where it's difficult to change the plumbing infrastructure.

Let’s take a closer look at above-floor grinder pump systems as an effective, cost-efficient alternative to trenching.

Pre-assembled grinding pump systems are capable of discharging wastewater from multiple fixtures. No matter how big your project is, for commercial or residential purposes, above or below ground, one or two motors, an above-floor grinder pump offers a cost-effective alternative to trenching.

Consider Saniflo’s Sanicubic range of pre-assembled, simplex and duplex pump systems. The Sanicubic Vortex Series features a vortex-type impeller that delivers clog-free handling of solids up to two inches in diameter. The series is engineered for highly demanding, rugged-duty applications that involve much larger or harder objects than what is typically flushed down a toilet.

The Vortex Series is intended to provide above-floor drainage for multiple plumbing fixtures for an entire residential or commercial structure, thus eliminating the need for costlier and less convenient trenching or pit installations.

Two models are available: the Sanicubic 1VX, equipped with a single, 1.5-horsepower motor (“simplex”); and the Sanicubic 2VX, equipped with two such motors (“duplex”). Both lift stations are capable of discharging through two-inch or four-inch rigid pipe and offer a shut-off head of 43 feet. Both are meant to be connected to a high voltage (220V-240V) but can be connected to 208 V (min).

Real-world applications

In a recent application involving a 10,000-square-foot building used as a daycare, one end of the structure had no available plumbing. The daycare tenant, therefore, had to add six bathrooms to meet its needs. Four of those bathrooms were promptly placed on the exterior wall using rear discharge toilets, but the two bathrooms for the interior presented a challenge.

Initially, another plumber tried to solve the problem by installing a smaller and less powerful drain pump for the two interior facilities, but it proved unreliable. As the second plumber on the job, Nathan Farmer of Farmer’s Plumbing realized that a different type of drainage solution was needed and contacted Saniflo for assistance.

One of the issues the daycare faced was the children and facility staff's high usage of these bathrooms and their misuse. “Some of the occupants were flushing items such as paper towels and other materials that were not suitable for the existing system, causing clogs and other problems,” explains Farmer, identifying the problem that needed to be addressed.

Realizing that a more reliable solution was required, Farmer recommended a bigger, more rugged pump model to meet the daycare’s demanding requirements.

With the help of a local supplier, the Saniflo Sanicubic 1 VX heavy-duty duplex Vortex system was suggested to Farmer as the solution.

Farmer readily admits that he was in uncharted territory despite his years of plumbing experience, but he faced the challenge head-on with careful planning and skill.

Each of the two bathrooms has two toilets and two sinks. A small storage closet is tucked away in the corner of each bathroom. Additionally, a kitchen sink is approximately 10 feet from the toilets.

The wastewater from the two bathrooms and the kitchen sink feeds into the vortex pump unit. The unit pumps the wastewater vertically via a pipe located in the attic space. Then, it travels with a 1/8 per foot slope to the main sewer line outside the building, discharging a total horizontal distance of 30 feet. The pumping unit is conveniently located in the small storage closet, a central location that serves all fixtures efficiently.

The plumbing team replaced the original 1.5-inch discharge pipe for the previous pump with a two-inch line to optimize the system’s performance. This upgrade ensures a smooth effluent flow and enhances the system’s functionality.

The installation process was quick and efficient, taking just one hour, reports Farmer. While removing the previous pump, the positioning of the former discharge line aligned perfectly with the new Vortex unit, saving labor and maximizing system performance.

Since the installation, the system has operated flawlessly, without blockages or operational hiccups caused by flushing inappropriate items. This outstanding performance is a testament to the quality of Farmer’s planning and workmanship.

Next time you have the “opportunity” to bust through a concrete floor to run piping or bury an ejector pump, we hope you’ll take a few minutes to recall the red flags associated and the much more convenient alternative. Why keep doing things the old-school way when there’s an easier and less expensive alternative that will leave your customer happier and your bank account fuller?

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!